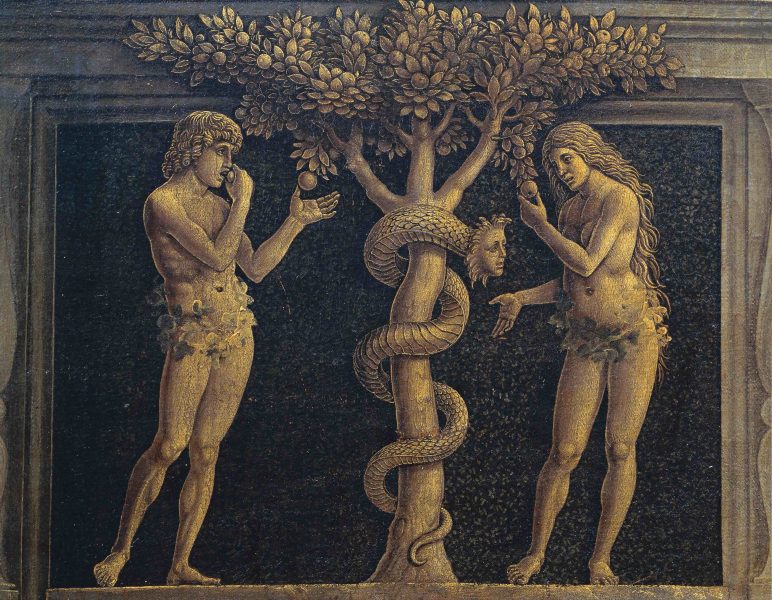

And when the woman saw, that the tree was good for food, and that it was pleasant to the eyes, and a tree to be desired to make one wise, she tooke of the fruit thereof, and did eate, and gaue also vnto her husband with her, and hee did eate.

Genesis 3.6

Creation myths rarely sound out the language of childbirth, preferring instead ecclesial narrative, pronouncing man exiled anima, who having tooke of the fruit, now plumbs the depths of being. The archeological record though speaks of else, placing man marooned orphan attempting overcome the dearth that marks his existence through heroic struggle. The dissonance never more apparent than the seven ages of man. The newborn emerging from womb gasping for breadth, smeared in excreta, writhing in pain—set ablaze in inferno of decay and time. The unformed body appearing before creation clasping, helpless, and beyond communion. The unsheathed mind aware only of the infinite present, of the coarse air, the piercing noise, the blinding light. And still that the infant should in the first confront life with gleam of curiosity is perhaps first clue to the wanderlust that sparks adventure. That man should in the last seek refuge in the ever after proof of truancy. Because from beginning to end the universe stands antagonist to his being.

BIBLIOGRAPHY: 1. Mantegna, Andrea. Madonna della Vittoria. 1496. tempera on canvas. Louvre Museum, Paris. 2. The Holy Bible, 1611 Edition: King James Version. Peabody: Hendrickson, 2011. Print. 3. Śaṅkarācāryaḥ, Ādi. The Isa, Kena & Mundaka. Upanishads and Sri Sankara's commentary: First Volume. Translated by S. Sitarama Sastri, Madras: V.C. Seshacharri, 1905. Print. Verse 3.1.1, Shankara’s Commentary: The Para vidya has been explained, by which the immortal ‘purusa’ or the Truth could be known, by whose knowledge the cause of Samsara, such as the knot of the heart, etc., can be totally destroyed. Yoga which is the means to the realization of the Brahman has also been explained by an illustration “taking the bow and the rest.” Now the subsequent portion is intended to inculcate the auxiliary helps to that yoga, as truth, etc. Chiefly, the truth is here determined by another mode, as it is extremely difficult to realize it. Here, though already done, a mantra (brief) as an aphorism is introduced for the purpose of ascertaining the absolute entity. Suparnau, two of good motion or two birds; (the “word Suparna” being used to denote birds generally); Sayujau inseparable, constant, companions; Sakhayau, bearing the same name or having the same cause of manifestation. Being thus, they are perched on the same tree (‘same,’ because the place where they could be perceived is identical). ‘Tree’ here means ‘body;’ because of the similitude in their liability to be cut or destroyed. Parishasvajate, embraced; just as birds go to the same tree for tasting the fruits. This tree as is well known has its root high up (i.e., in Brahman) and its branches (prana, etc..) downwards; it is transitory and has its source in Avyakta (maya). It is named Kshetra and in it bang the fruits of the karma of all living things. It is here that the Atman, conditioned in the subtle body to which ignorance, desire, karma and their unmanifested tendencies cling, and Isvara are perched like birds. Of these two so perched, one, i.e., kshetrajna occupying the subtle body eats, i.e., tastes from ignorance the fruits of karma marked as happiness and misery, palatable in many and diversified modes; the other, i.e., tbe lord, eternal, pure, intelligent and free in his nature, omniscient and conditioned by maya does not eat; for, lie is the director of both the eater and the thing eaten, by the fact of Ids mere existence as the eternal witness (of all); not tasting, he merely looks on; for, his mere witnessing is direction, as in the case of a king.