Wherever a moving ship may be heading, at its bow will always be seen the swirl of the wave it cuts through. For people on the ship, the movement of that swirl will be the only noticeable movement. Only by following closely, moment by moment, the movement of that swirl and comparing that movement with the movement of the ship, will we realize that at every moment the movement of the swirl is determined by the movement of the ship, and that we were misled by the fact that we ourselves were imperceptibly moving.

Tolstoy, War and Peace

AT THE END of War and Peace (1867), Leo Tolstoy, unhappy with the state of history, delves into the question at the heart of every why: What force moves people? Tolstoy begins with the traditional view of history—that divinity acts through individual men to guide history to a predestined goal. Tolstoy contrasts the traditional view with the modern view of history, “that (1) peoples are guided by individual men, and (2) there exists a certain goal towards which peoples and mankind move (Tolstoy 1806).“ Tolstoy takes particular aim at the idea “all things that we see standing accomplished in the world are properly the outer material result, the practical realisation and embodiment, of Thoughts that dwelt in the Great Men sent into the world (Carlyle 1-2),“ faulting it for obscuring the innumerable causes that bear on historical events. Tolstoy himself takes a markedly different view, proposing, the Great Man, like the swirl at the bow of the ship, only appears at the head of events, but has little bearing on the course of history. Tolstoy ends on the idea the movements of mankind and of peoples are governed by as yet undiscovered Natural Laws.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

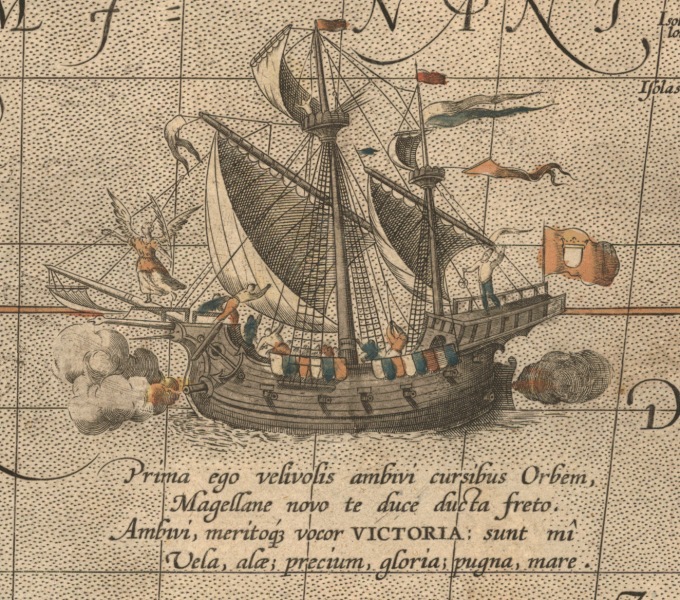

1. Ortelius, Abraham. "Maris Pacifici Quod Vulgo Mar Del Zur." Copper engraving, 1589.

2. Tolstoy, Leo Nikolayevich. War and Peace. Translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, New York: Vintage Books, 2007. Print.